Composer-producer Andy Ingamells on storytelling, Station Clock and the second city

For the final piece of his foundation art course in 2007, Andy Ingamells walked 12 miles from his house in Sheffield to a gallery in Chesterfield, playing the trumpet the entire way.

Upon arriving at his destination, Andy put his trumpet on a mannequin and left an audio recording of his performance sounding aloud, one of the first indications of a mould-breaking musician who would go on to repeatedly strike a thought-provoking balance between visual and sonic artistry.

Early talent was not matched by confidence though.

“When I was growing up, I always used to get stage fright because I was terrified that people in the audience knew exactly what the piece was supposed to sound like and that I would make a mistake and everyone would know and I would be embarrassed,” the Station Clock composer-producer explained.

“But when I started composing music, I didn’t get stage fright anymore because if I’d written a piece it didn’t matter if it went wrong. I was the person who’d written it.”

Always fascinated by visual art, Andy spent his formative years playing in brass bands and would perform the Last Post at people’s funerals in Sheffield.

This early connection to brass instruments reappeared in his later career too, from collaborating with Susan Philipsz on her exhibition, War Damaged Musical Instruments to the Up Down Left Right project Andy worked on with The Salvation Army brass band in 2017.

The latter work in particular exemplifies Andy’s ingenuity; the musician invited 40 members of the public to spontaneously conduct the brass band over one day, regardless of their musical experience.

The result was a beautifully moving score which expressed the different relationships created between each composer and the band.

“If the person did a down beat then the band would start playing but if they didn’t go to the second position, the band would just carry on holding that first note. The conductor was deconstructing the music,” Andy recalled.

“It was really cool to see all these different people reacting to the band. There was a sign language interpreter and when she came on, she put the baton down really purposefully and did all these hand gestures. The band then just started blowing through their instruments, making these air sounds.

“Just seeing all these different reactions to people conducting the band and interacting was a real highlight for me.”

Such is the visionary authenticity of Andy’s portfolio that his work has been performed all over the world, from Denmark to Derry, and is a collection which the musician summarised in three words: reading, character and playing.

“When you’re watching a classical performer play on stage you’re watching them in an act of reading. I quite like the theatre of someone reading something on stage but responding in sound.

“For the character part, I sometimes might dress up as a composer from the past, like Beethoven, and create work on my laptop as if Beethoven is writing it.

“With the playing aspect, I like to make little games out of stuff. I do a piece where I’ve got a big balloon drop set up and have violin players come in who have all got pins on their bows and play really fast, and then the balloons drop with the audience crowding round throwing the balloons to create the percussion part.”

Andy’s ability to put aside the classical textbook and innovatively bring out a story through music is a skill which has undoubtedly enriched the process of recording voices for Station Clock.

Originally brought into the project by fellow artist Bobbie-Jane Gardener to assist with the initial workshops, Andy has evolved into the sole composer-producer for Station Clock, helping to document hundreds of voices over the course of several years.

“There have been so many people involved. We’ve had all the gallery assistants, all the production assistants, all the technicians doing the recordings, it has been a real group effort.”

Reflecting on his personal highlights from the recording sessions, Andy outlined how he had enjoyed meeting so many people and watching them get the chance to be in a recording studio.

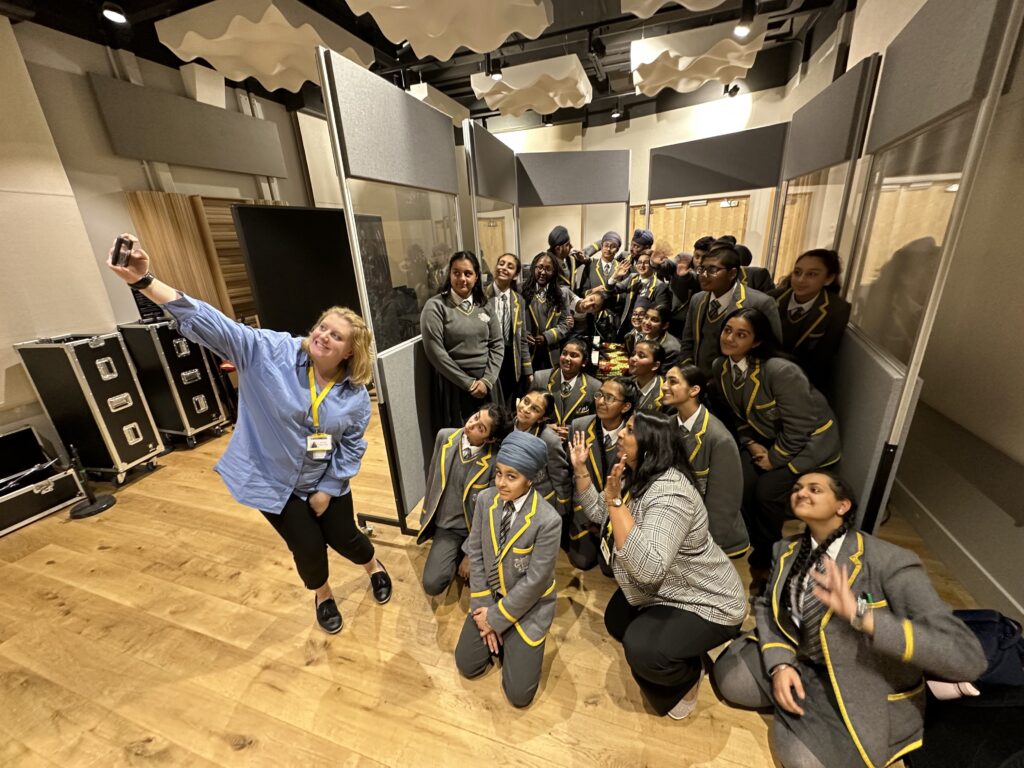

“I really loved the energy when a big school group would come in. I’d be in the main live room, looking out through the glass, and just see twenty children all stood around having a great time and listening to each other sing.

“Loads of people were asking questions about when the clock was going to be built, how old they were going to be when it was built and that kind of thing.

“I loved participating in the project too, I think I felt like a participant in it as well. I loved that aspect of being together with people and singing.”

With the 1,092 required voices now captured, Andy has begun categorising and developing the tones into the clock’s hourly compilations.

Describing the different folders of recordings as a “palette of colours”, the composer-producer explained how he has been given permission to arrange the notes as he sees fit.

“I feel really privileged to be trusted with such a big project. I always felt that my career fell in between visual art and music and I never really felt at home in either place. This project made me feel at home and accepted and I’m really grateful for that.”

This embrace of his work is something he has experienced in the city as a whole too.

“Birmingham has been my home for a long time, it’s the place where I felt like I could really be myself. I felt like I found who I am in Birmingham and I have always felt I, and my work, have been supported in Birmingham.

“It’s just a really supportive place, it supports difference and people who don’t make conventional stuff, people who want to work on the margins of different disciplines and different crafts.”

Looking forward, Andy is hopeful that future generations of Birmingham will continue to adopt and adapt Station Clock, perhaps even turning it into another piece of art in decades to come.

“I wonder if it will change over time. I wonder if perhaps on the 100th anniversary of it, people will re-record another 1,092 voices when everyone who has recorded on the clock has passed on.

“I hope that people do something with it and it lives on.”